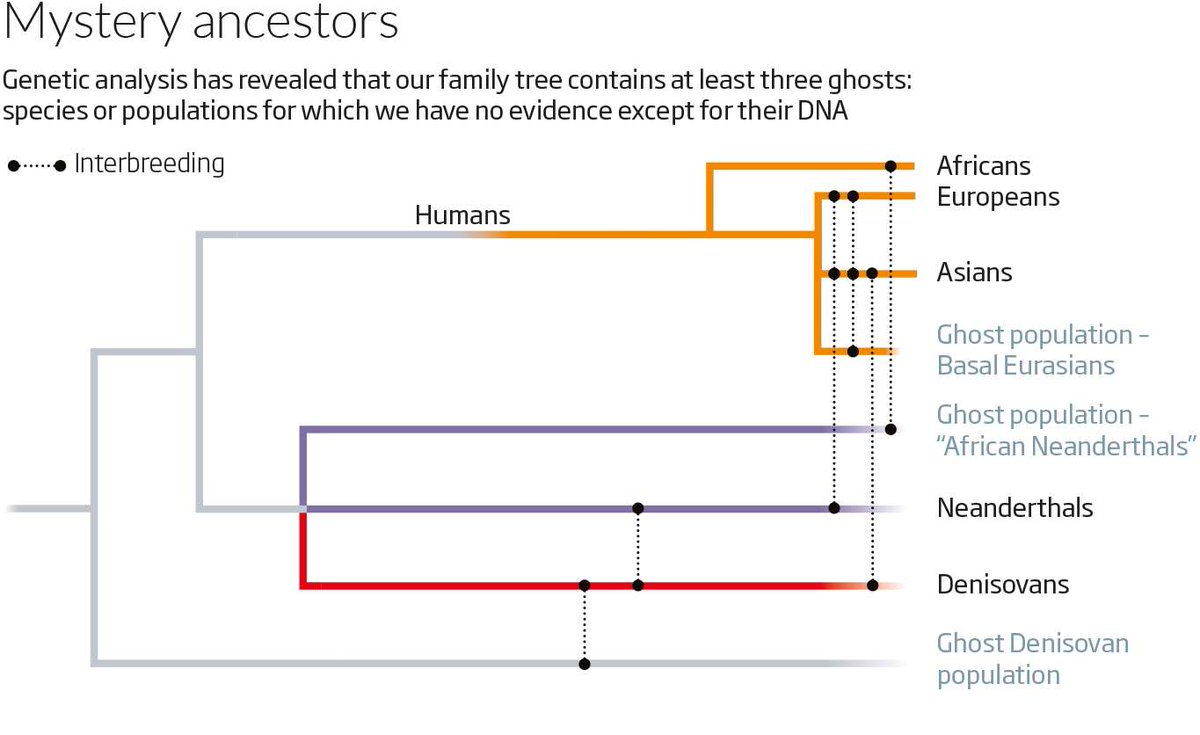

Hominins lived in China 2.1 million years ago

A new stone tool find pushes back the date for hominin dispersal beyond Africa.

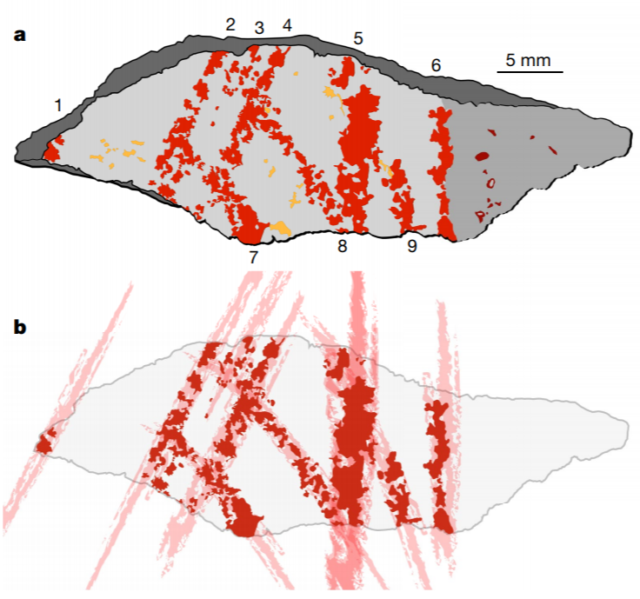

Early hominins lived here, near Shangchen in China's southern Loess Plateau, 2.1 million years ago.

Early hominins ventured out into the world beyond Africa even earlier than we've given them credit for, according to a new stone-tool find on the southern edge of China's Loess Plateau.

Hominins—the lineage of apes that eventually came to include humans—began making recognizable stone tools about 3 million years ago. Before that date, we know that our early relatives inhabited a place only if we find their bones or, in rarer cases, their footprints. But stone tools offer a more durable, more abundant calling card. Pick up a stone flake or scraper—or a core of flint or chert with obvious scars from flintknapping—and you know that someone made this object. Someone was here.

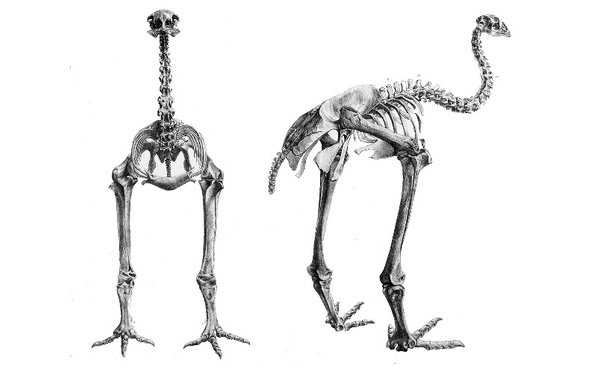

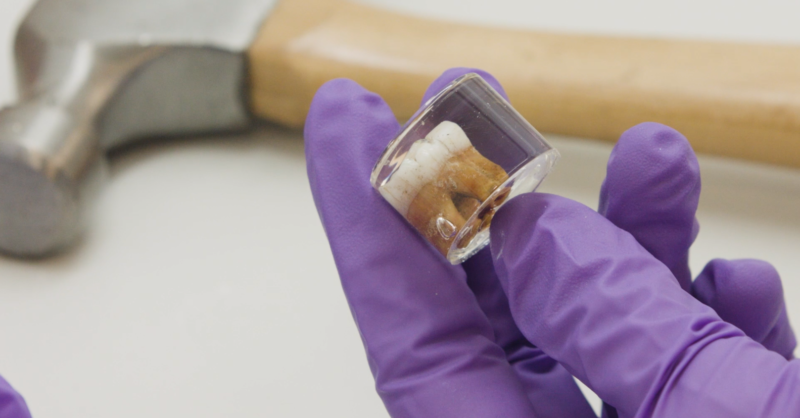

And that's exactly what archaeologists led by Zhaoyu Zhu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences found in a 2.1 million-year-old layer of ancient wind-blown sediment in China's southern Loess Plateau: a collection of stone cores, flakes, scrapers, borers, and points, as well as a couple of damaged hammerstones. The tools' style strongly resembles stone tools found at sites of about the same age in Africa, made by early human relatives like

Homo erectus.

The find pushes back the earliest evidence for hominins outside Africa, which had been a 1.85 to 1.77 million-year-old group of

Homo erectus bones and stone tools at a site in Dmanisi, Georgia, not far from the Armenian border. The location in China means that hominins may have ventured beyond the warm tropics of Africa into the less-certain environments of Eurasia a few hundred thousand years earlier than archaeologists previously thought.